Created in the 1950s in the Japanese Toyota factories, Lean has established itself as an efficient, friendly approach to production management aimed at reducing waste while ensuring continuous improvement.

Initially designed for industry, Lean is eminently applicable in a variety of fields – for example, one might speak of Lean Management, Lean Startup or Lean IT, depending on the field of application. More recent frameworks, such as Scrum (which originated in Agility, another movement that emerged alongside Lean), are now directly and explicitly linked to Lean. This exposure to new horizons enables us to devise new uses for the various Lean tools and practices, including Kanban, Mudas, Kaizen and 5S work sites. In this article, we’ll focus on the latter (5S projects), and specifically on how I used it to manage a Product Backlog in a Scrum context… but first, let’s take a look back at the origins of its adoption in industry.

5S as a Lean tool and in industry

5S is a Lean tool used mainly in the industrial environment, and more particularly as a way of organising shops and workshops. For example, 5S can be used to organise consumables (screws, sensors, motors, etc.) in a way that is clear to everyone.

Lean describes 5S as a method of improvement; it aims above all to reduce waste, particularly in terms of time wasted, by simplifying everything that can be simplified and removing the unnecessary.

The five 5S operations

Like many Lean tools, the terms have Japanese names. 5S consists of 5 steps to be performed in sequence, in the following order:

- Seiri (Organise): Sort and eliminate the unnecessary

- Seiton (Order): Set things in order

- Seiso (Clean): Make things Shine

- Seiketsu (Schedule): set regular Standards

- Shitsuke (Self-discipline, or education): Sustain progress

- Seiri : the first step is to identify and remove what is unnecessary. Anything that is not regularly used should be recycled, thrown away or archived. Identify what should be placed in closest proximity to the work area, because this is what should be used first or most regularly. The aim is to increase concentration by removing distractions and interruptions.

- Seiton : the aim of this second step is to avoid wasting time and energy by arranging the elements in as logical a way as possible. Seiton is often paraphrased as “A place for everything, and everything in its place.” Similar items are thus grouped together by categorising them. The result of this step is a working environment in which searches for a specific item are facilitated by the organisational structure. It is preferable, but not compulsory, to manage using the FIFO principle (“First In, First Out”; e.g. as in a queue), as opposed to LIFO (“Last In, First Out”, as in a pile of plates).

- Seiso : for this third stage, we will do our best to avoid future problems by making them as easy as possible to detect. So we’ll tidy our working environment and clean up/repair things where necessary. This is the first step towards self-management and constant maintenance of the working environment and the things in it.

- Seiketsu : this fourth stage is the standardisation stage, which involves defining the rules that will enable us to avoid disorder wherever possible. It is advisable to make maximum use of visual management and labelling. For example, in a workshop, spray paint the workbench to show an outline for each tool, making it easy to see where to put a tool and/or whether any tool is missing.

- Shitsuke : the aim of this fifth and final step is to educate everyone involved in the work environment to ensure that following 5S becomes a daily habit. To prevent a 5S failure (see below), everyone needs to adhere to the rules of standardisation and tidiness that have been put in place. This is why it is advisable not to impose these rules, but to agree them jointly with the individuals in question, the aim being to maintain them over time for as long as possible to avoid having to perform another 5S later.

Équivalent en français : ORDRE

5S is also known in French by the acronym ORDRE:

- Ordonner (ordering)

- Ranger (tidying)

- Dépoussiérer (dusting)/ Découvrir (discovering) anomalies

- Rendre évident (making it obvious)

- Être rigoureux (being rigorous)

Applying 5S to everyday life

What if I told you that you’re most likely applying 5S principles naturally and daily at home without even realizing it?

Don’t you see how?

Maybe if I asked you how you organise your food or dishes? For example, I’m sure forks have a specific place in your home, as do plates, glasses, knives, etc. You have identified specific storage spaces for each of these items, and if a spoon accidentally ends up where the forks live, you think something has gone wrong, and you’ll probably put it right fairly quickly. Similarly, you wouldn’t put a dirty fork away among the clean ones.

Think about this the next time you put away your cutlery and crockery; look at each thing you do, and try to link it to each of the 5S steps.

Managing a Product Backlog with 5S

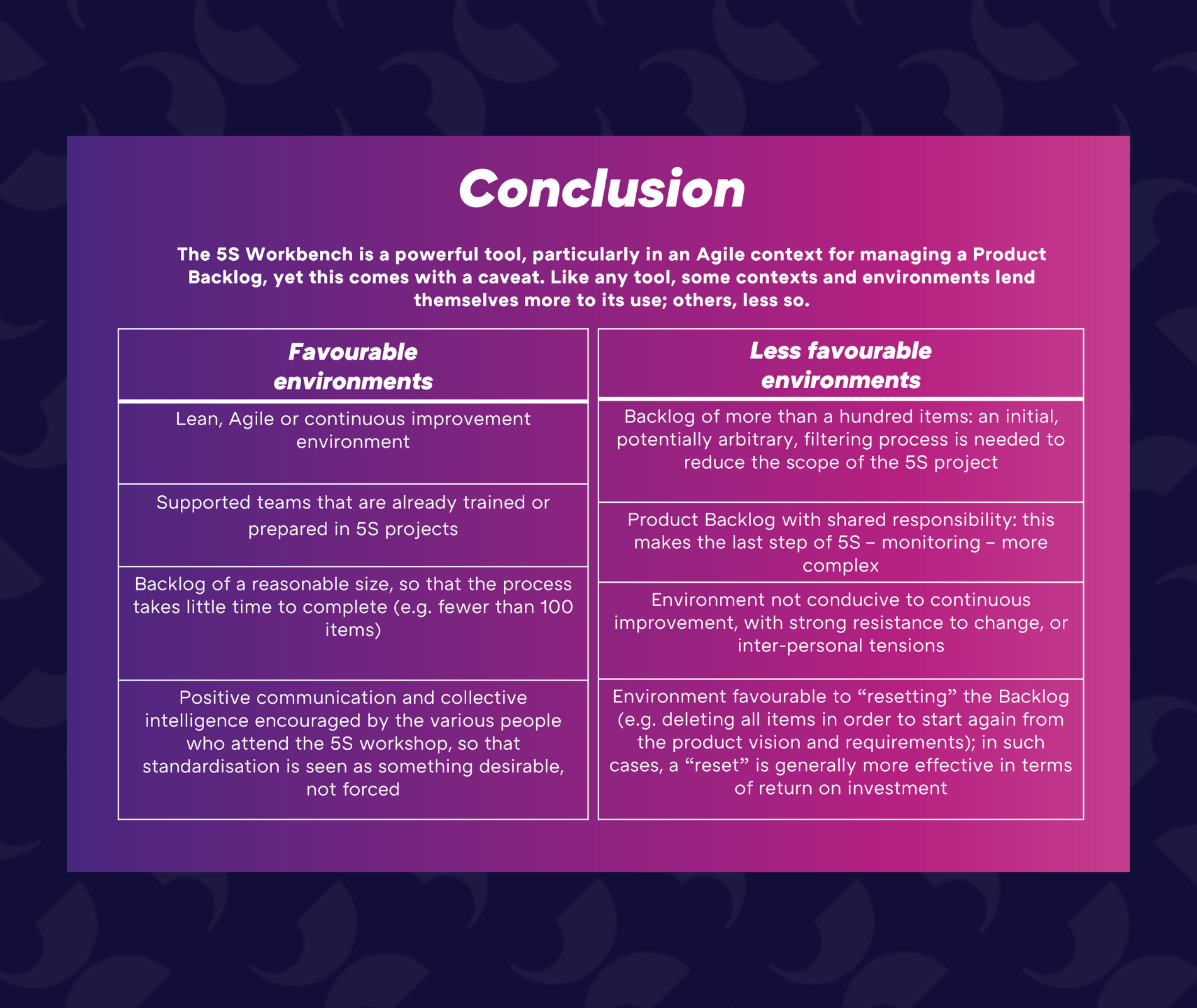

5S is fully applicable to managing a backlog, or to reorganising it when management has failed. I personally introduced 5S in my professional sphere to achieve this goal. The most recent time I used it was on a backlog consisting of more than a hundred items, not all of which were defined according to the same nomenclature, with or without descriptions and containing obsolete or important tasks… the operation required the input of a good part of the team and took a whole day.

Obviously, before you try something similar yourself, I’d advise you to bear in mind that it’s really not a great idea to start 5S from scratch on a regular basis, and that you need discipline to keep the system in perfect working order. So it’s important to ensure that the people concerned understand that this process is costly and painful, but becomes irrevocably necessary once the disorder has been allowed to develop.

In short, this is the strategy used, hand in hand with 5S, to effectively impose order on a backlog:

- Seiri: remove the unnecessary. For example, although this may seem brutal, we can set a date upon which we consider the items in the Backlog to have become obsolete, and archive all items older than this date (for example, more than a year): items that are genuinely necessary will come up again in daily business, and it will be easier for us to assess the cost/benefit ratio of dealing with them. To be less brutal, you can also go through each item one by one with a representative of the client or the users; or, failing that, with a team member who understands all the complexities of the business… but this can quickly become time-consuming, which is why I recommend mixing these two approaches.

- Seiton: Set things in order. Once the first step has been completed, each item will be reviewed again in order, if necessary, to place it in the right Backlog (assuming that the initial Backlog relates to several products), and prioritise the tasks between them. If there is no way of quickly and easily establishing a business value and/or story (effort) points, it’s a good idea to rank the items you know most about first, and the vaguest items last.

- Seiso: Make it sparkle. Next comes the cleaning phase, the aim of which is to make it easier to detect anomalies and correct them if found. Personally, I use this stage to add any descriptive elements that may be missing, and rewrite the item in the form of a User Story if necessary.

- Seiketsu: Standardise. This can, for example, be done (by a Product Owner, who has sole responsibility for the Backlog) by setting up labels and filters, addition rules (by default, items are added to the top or bottom of the Backlog), rules for prioritising items, a buffer space for any item that is not ready (be careful, however, that this does not become a second Backlog, so make sure that the life of each item in this buffer space is as short as possible), a Definition of Ready, or any other adjustment that you deem necessary. Beware: standardisation must be kept simple, in order to ensure that it is as simple as possible to comply with it.

- Shitsuke: educate. For the last step – which, in my opinion, is also the most important one – you need to explain how the Backlog works to everyone who needs to see it (team members, but also other parties such as managers and decision makers). The best thing to do is to start by noting the failure and constructing the standardisation rules with the relevant parties to ultimately produce a solid practical proposal (using visual management, for example, which makes the management rules understandable at a glance, or perhaps automation, so that you don’t even have to think about them). This proposal should not be set in stone: continuous improvement must of course be encouraged, but we must remain vigilant about the strict application of 5S and therefore of the jointly determined rules, even if this entails an evolution over time as experience is gained, in order to avoid any drift that would lead to the failure of the 5S system.

Why isn’t our 5S working?

It often happens that the application of 5S lasts only for a short time before we return to our good old disorder: because chaos leads to chaos, it only takes one small exception to the rule and all the good work of 5S can be destroyed in a few moments. For example, the small User Story that doesn’t get properly filed in the Backlog, because we say we’ll do it “later”… and unfortunately, this means it will never get filed because, as Leblanc’s law stipulates, “later” means “never”.

This most often happens because the 5S process has not been completed. Following the fourth step of standardisation (Seiketsu), many people will stop there and say that they finally have a tidy, practical backlog or workshop to use, ignoring the step that I think is the most important: Shitsuke, or education (self-discipline) about working practices. Because this stage is neglected, for reasons of budgetary constraint or because it is not considered necessary, it inevitably leads to the return of disorder (a User Story that is not placed in the Backlog, followed by a second one because there was already one there, etc.). Note the following regarding the Backlog (as an analogy with Agile frameworks): Scrum requires a Product Owner, which greatly facilitates the last and most difficult stage of 5S, since the Product Owner is the only one who takes action on the Backlog and therefore ensures that 5S is applied. Remember, however, that Scrum requires that the content of the Product Backlog must be publicised sufficiently clearly to all concerned (Scrum team, but also stakeholders), so it is important to ensure that, despite the fact the Product Owner bears sole responsibility for the management of the Product Backlog, the standardisation of the backlog is still the result of a shared process based on collective intelligence.